Vermont Quits War on Drugs to Treat Heroin Abuse as Health Issue

Harm Reduction

911 Good Samaritan Law

Naloxone

Overdose Prevention

Addiction Law, History and Public Policy Articles

Drug War

Drug Policy Reform

Overview

Originally Published: 08/26/2014

Post Date: 08/26/2014

Source Publication: Click here

Similar Articles: See the similar article

Summary/Abstract

Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin devoted his entire State of the State address in January to what he called Vermont’s “full-blown heroin crisis.” Since 2000, he said, the state had seen a 250 percent increase in addicts receiving treatment. The courts were swamped with heroin-related cases. In 2013 the number of people charged with heroin trafficking in federal court in Vermont increased 135 percent from the year before, according to federal records. Shumlin, a Democrat, urged the legislature to approve a new set of drug policies that go beyond the never-ending cat-and-mouse between cops and dealers. Along with a crackdown on traffickers, he proposed rigorous addiction prevention programs in schools and doctors’ offices, as well as more rehabilitation options for addicts. “We must address it as a public health crisis,” Shumlin said, “providing treatment and support rather than simply doling out punishment, claiming victory, and moving on to our next conviction.”

Content

Vermont has passed a battery of reforms that have turned the tiny state of about 627,000 people into a national proving ground for a less punitive approach to getting hard drugs under control. Under policies now in effect or soon to take hold, people caught using or in possession of heroin will be offered the chance to avoid prosecution by enrolling in treatment. Addicts, including some prisoners, will have greater access to synthetic heroin substitutes to help them reduce their dependency on illegal narcotics or kick the habit. A good Samaritan law will shield heroin users from arrest when they call an ambulance to help someone who’s overdosed. The drug naloxone, which can reverse the effects of a heroin or opioid overdose, will be carried by cops, EMTs, and state troopers. It will also be available at pharmacies without a prescription. “This is an experiment,” Shumlin says. “And we’re not going to really know the results for a while.”

|

|

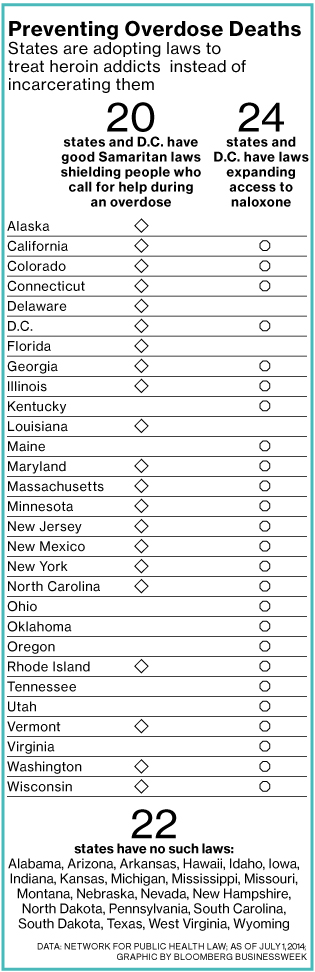

Leniency won’t apply to traffickers or major drug suppliers. “The culture hasn’t shifted if you’re a heroin dealer,” says South Burlington Police Chief Trevor Whipple. “If you’re trafficking hundreds of bags of heroin a day in our community, we’re probably not going to [think] much about, you know, ‘How can we help you?’ ” Vermont isn’t the first place to test such harm-reduction policies, as they’ve come to be known. About half of U.S. states allow some distribution of naloxone, and at least 20 have a version of the good Samaritan law. Cities including Chicago, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee offer certain people charged with drug crimes alternatives to incarceration. But Vermont is going further, investing in harm reduction as a primary method of battling heroin addiction and drug-related crime statewide. In an e-mail, Lindsay LaSalle, an attorney for the Drug Policy Alliance who has helped draft legislation in several states, said, “Vermont has emerged as the leading state in the country in addressing opioid overdose through broadscale and comprehensive overdose prevention legislation.” Harm reduction has typically found broader support among academics who study addiction and criminal justice than among cops and politicians. “The way I was brought up is that people have to accept responsibility for their actions,” says Lamoille County Sheriff Roger Marcoux Jr., who’s fine with having his officers carry naloxone but skeptical of letting people caught with illegal narcotics off the hook. “When I arrest somebody for doing heroin or having heroin, [and] he tells me, ‘It’s not my fault, I’m an addict,’ I don’t buy that.”Despite such skepticism, Vermont’s new policies passed the overwhelmingly Democratic legislature without much opposition from law enforcement groups. Even Marcoux says he’s “got an open mind to it” and will be “waiting to see what statistics tell us about the success rate.” One champion of the over-the-counter naloxone legislation was Republican Representative Thomas Burditt, a libertarian. “I was surprised,” he says, because the new naloxone rule “just flew right through.” He calls it “a no-brainer,” and says he got no pushback from voters. “As everybody knows, the war on drugs is lost, pretty much. It’s time to go down a new road.” Vermont is a mostly liberal state with low unemployment and among the lowest violent crime rates in the country. But its drug problems reflect the larger national trend. Rapidly rising prison costs and drug-related incarceration rates have made treatment increasingly popular even among some conservatives. Daniel Raymond, policy director of the advocacy group Harm Reduction Coalition, says crack cocaine “was viewed as an urban inner city problem among people of color,” but with heroin “there’s a recognition that the drug problem isn’t ‘over there.’ ” |

The Vermont experiment has the blessing of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, which has been losing the war on drugs for decades. In March, Gil Kerlikowske, then President Obama’s drug czar, joined Shumlin to announce expanded naloxone access. After visiting a local treatment facility, he declared himself “full of a lot of optimism,” and “full of a lot of hope after having listened to everyone here about the approach that this has taken.” U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder has called on all first responders “to train and equip their men and women on the front lines” to use the medicine. On July 31 he announced plans for federal first responders to carry it.

The people who pushed Vermont’s new drug policies are mindful that the initiatives could flop. “Now we’ve got to pull it off, and we’ve got to demonstrate that it does work, that it is going to reduce recidivism, and it is going to achieve the kind of savings,” says Chittenden County State’s Attorney T.J. Donovan. “End of the day, this whole thing could implode, you know—but I’m not sure we could do any worse than what we’ve done these last couple of decades.”