Narcotics Anonymous - Its History and Culture

Overview

Originally Published: 07/14/2015

Post Date: 07/14/2015

by William White, Chris Budnick, and Boyd Pickard

Attachment Files

PDF | Narcotics Anonymous - Its History and Culture

Summary/Abstract

Narcotics Anonymous - Its History and Culture by William White, Chris Budnick and Boyd Pickard

Content

NARCOTICS ANONYMOUS: ITS HISTORY AND CULTURE

William White, Chris Budnick, and Boyd Pickard

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) stands as the benchmark by which all other addiction recovery mutual aid societies are measured due to its longevity, national and international dispersion, size of its membership, adaptation of its program to other problems of living, influence on professionally-directed addiction treatment, cultural visibility, and the growing number of scientific studies on its active ingredients and their effects on long-term recovery. That said, other addiction recovery mutual aid societies are growing in number and in the diversity of their philosophies and methods. A lthough Narcotics Anonymous (NA) was one of the earliest adaptations of the AA program, NA remains less well-known among addiction professionals. The purpose of this paper, abridged from the forthcoming new edition of Slaying the Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, is to provide an overview of the history and culture of NA and to distinguish the NA program from AA and other recovery mutual aid societies.

Introduction

Addiction recovery mutual aid societies rise within unique historical contexts that can exert profound and prolonged effects on their character. Just as the birth of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is best understood in the context of the repeal of Prohibition and the challenges of the Great Depression, the history of Narcotics Anonymous (NA) is best understood in the cultural context of the 1950s. It was in this decade that the notion of “good” drugs and “bad” drugs became fully crystallized. Alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine achieved the status of culturally celebrated drugs as an exploding pharmaceutical industry poured out millions of over-the-counter and prescription psychoactive drugs. H eroin and cannabis became increasingly demonized in the wake of a post-World War II opiate addiction epidemic. Social panic triggered harsh new anti-drug laws. Known addicts were arrested for “internal possession” and prohibited from associating via “loitering addict” laws. Any gathering of recovering addicts for mutual support was subjected to regular police surveillance. Mid-century treatments for addiction included electroconvulsive therapy (“shock treatment”), psychosurgery (prefrontal lobotomies), and prolonged institutionalization. This is the inhospitable soil in which NA grew.

Two 1935 events were critical to the eventual rise of recovery mutual aid groups for drug addiction: the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous and its subsequent outreach to hospitals and prisons, and the opening of the first federal “Narcotics Farm” (prison hospital) in Lexington, Kentucky.1 This article will explore the history of NA, but read carefully, because there was more than one NA, only one of which survived to carry its message of hope to addicts around the world.

Addiction Recovery in AA: Dr. Tom M.

Within four years of the founding of AA, individuals addicted to opiates and other drugs began exploring whether mutual support and practicing AA’s 12 Steps might offer a means of recovery. Ground zero for transmission of the AA program to drug addicts was the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. Opened May 25, 1935, and widely known as the “Narcotics Farm” or “Narco,” this prison/hospital treated people addicted to narcotics who had been sentenced for federal drug crimes and those who applied for voluntary treatment.2 One enduring outcome of Narco was the discovery there that the program of Alcoholics Anonymous could be successfully applied to other drug addictions.

Dr. Tom, a physician who had been an alcoholic before developing a twelve-year addiction to morphine, entered the Narcotics Farm in 1939 to take “the cure” and while there, found a newly published book—Alcoholics Anonymous—that changed his life.3 Upon returning to Shelby, North Carolina, in the fall of 1939, Dr. Tom M. and three other men held the first meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous in North Carolina.4 Dr. Tom M. is the first known person to achieve sustained recovery from morphine addiction through Alcoholics Anonymous,5 and the Shelby group became a resource for AA General Headquarters in New York to respond to inquiries about a solution for drug addiction.6

Early experiments in applying AA’s Twelve Steps to the problem of opiate addiction span a period in which AA was becoming increasingly conscious of “other drugs.” AA member “Doc N.” wrote a letter to the AA Grapevine in 1944 suggesting a “hopheads corner” through which AA members who were also recovering from narcotic addiction could share their experience, strength, and hope. 7 This was followed by a long series of Grapevine articles about drugs (narcotics, sedatives, tranquilizers, and amphetamines), including a 1945 warning from AA co-founder Bill W. about the dangers of “goofballs” in which he acknowledged that he had once nearly killed himself with chloral hydrate. Early Grapevine articles became the basis for a series of AA pamphlets, beginning in 1948 with Sedatives: Are they an A.A. Problem?8 The key, sometimes contradictory, points in these early (1948, 1952) pamphlets were that:

- The alcoholic has a “special susceptibility to habit-forming drugs of all types” (1952, p. 18).

- Pills often lead to a resumption of drinking and loss of sobriety.

- A “pill jag” should be considered a slip.

- “The problems of the pill-taker are the same as those of the alcoholic” (1948, p. 8).

- Pill-takers are often psychopathic personalities, and AA members should only concern themselves with the “disease of alcoholism” (1948, p.9).

- AA members should refrain from administering sedatives as part of their 12-Step work— a not uncommon practice during this period.

The creation of the AA Grapevine in 1944 created the conduit through which addicts in AA first recognized their mutual presence and reached out to one another. During these early AA Grapevine exchanges, Dr. Tom suggested the possibility of establishing an AA group for addicts at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington.9 Two and a half years later, another AA member, Houston S., turned this idea into a reality.

Houston S. and Addicts Anonymous

AA outreach to prisons grew throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, as did prison-based AA groups. C urrent and former members of prison-based AA groups communicated through newsletters bearing such names as Alconaire (South Dakota), Alky Argot (Wisconsin), BAR-LESS (Indiana), The Corrector (Illinois), The Cloud Chaser (Minnesota), Cross Roads (Quebec, Canada), Eye Opener (Ohio), Folsomite (California), New View (New Hampshire), PenPointers (Minnesota), The Inventory (North Carolina), and The Signet (Virginia).10 The message of 12-Step recovery was first carried to addicts in prison by Houston S., an AA member without a history of other drug addictions.11

Houston S. developed a severe drinking problem after his training as a civil engineer at the Virginia Military Institute (1910-1914) and service in the U.S. Marine Corps (1918-1919).12 Family members repeatedly nursed him back to temporary health until Houston finally found permanent sobriety within AA in Montgomery, Alabama, in June 1944. F rom the earliest days of his recovery, he developed an evangelic fervor for helping others. To the occasional embarrassment of his family, Houston would share his recovery story to anyone at any time. Relatives tell many stories of the men he coached into recovery, temporarily housed, and helped financially, including paying for some to go to school. 13

In Montgomery, Houston helped a sales executive who was addicted to both alcohol and morphine. The sales executive stopped drinking through AA, but was unable to sustain recovery from his morphine addiction in spite of his prior treatment 15 As a result of

this experience, Houston became quite interested in AA members who were experiencing dual problems with alcohol and other drugs. When Houston was transferred to Frankfort, Kentucky in September 1946, just 20 miles from the Narcotics Farm,16 he called upon the medical director of the hospital, Dr. Victor Vogel, and suggested initiating a group similar to AA for addicts. W ith Dr. Vogel’s approval, Houston volunteered to help launch such a group inside the Lexington facility.

The first meeting of the new group was held on February 16, 1947. The members christened themselves Addicts Anonymous17 and met regularly at Lexington from 1947 until 1966. Houston remained involved with the group until his health began to fail in 1963. Through his liaison, AA groups in Kentucky as near as Frankfort and as far as Louisville provided regular volunteers to speak at the Addicts Anonymous meetings in Lexington.18,19 The sales executive who sparked Houston’s initial interest later returned to Lexington as a voluntary patient, began attending the Addicts Anonymous meetings, and went on to achieve stable recovery.20

Addicts Anonymous group meetings were completely voluntary. B y 1950, A ddicts Anonymous had a membership of more than 200 patients at the hospital.21 Membership declined by the 1960's when regular meeting attendance was roughly 35 men and 28 women.22 The meetings followed a format similar to AA meetings, and guidance for personal recovery was based on an adaptation of the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Within ten months of its founding, the secretary of Addicts Anonymous began correspondence with the Alcoholics Anonymous General Service Headquarters (GSH). I n a letter dated December 26, 1947, the secretary for the group requested that a letter and regular article about the group’s activities be published in the A.A. Grapevine. 23 General Service Headquarter staff wrote back stating that they had forwarded the letter to the Grapevine staff.24 Within two months, a letter appeared in the February 1948 issue of the Grapevine titled “Addicts Anonymous Ends First Year.”25

Early correspondence with the Addicts Anonymous group from employees of the General Service Headquarters was quite supportive. Charlotte L. wrote:

Naturally, all of us in AA want to do everything possible to help. We feel that your accomplishments in overcoming addiction through the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous, in special application to your problems, is a wonderful one and we share your joy. As many of you go into the outside world, carrying the message to others who suffer similar addiction, it is to be hoped that you will be the means of helping many others while maintaining your own recovered states. Please write to us as often as your time permits. Tell us how the group is getting along, how those on parole or completely released are making out, and above all, tell us what we can do to help.26

Another GSH staff member, Bobbie B., corresponded with Clarance B., secretary of the Addicts Anonymous group, in March and April of 1949. B obbie provided very supportive and encouraging words to Clarance and the members of the Addicts Anonymous group:

We, too, know that some of you who have recovered from drug addiction can be greatly helped by joining Alcoholics Anonymous groups. I, personally, know several who have made the grade and are some of our finest members. On the whole, I think our AA members are extremely tolerant and kind to all who come to them. And, why shouldn’t we be? We have been through some pretty harrowing times with our alcohol addiction and who are we to criticize others who may have used something else? May I send a little suggestion: give yourselves every break you can in obtaining recovery. Use any help no matter from where it comes. That’s what we alcoholics had to do so why not you people? Underneath it all, are we really so different? Doesn’t it add to the belief that underneath the few surface differences, we are much the same? You people are pioneers in this field of drug addiction. One day, Addicts Anonymous may be as well known as Alcoholics Anonymous. When that day comes, how grateful you all will be for the work and clear thinking of now. Just keep in mind that Bill and the very early members of AA went through the same problems of this misunderstanding that you people now face. And, most misunderstandings are based on ignorance.27

One of the most remarkable gestures of goodwill to the Addicts Anonymous group came when Bobbie mailed complimentary literature to Addicts Anonymous and suggested that, in the absence of their own literature, members could substitute the word drugs for alcohol when reading the AA material.28

Bill W. also corresponded with the Addicts Anonymous group, but tended in his letters to focus upon the differences and tension that existed between alcoholics and addicts—a subject we will return to later in more detail. In a letter to Clarance B., secretary of the Addicts Anonymous group, dated April 2, 1949, Bill writes:

While I make no doubt that underlying causes of alcohol and drug addiction are quite identical, it is a fact that the alcoholic feels himself a quite different, even a superior creature. To make the score a tie, it is probably true that the average addict looks down on the alcoholic. In fact I have seen that myself. Alcoholics and addicts are mutually exclusive and snobbish.29

Many of the Addicts Anonymous members who left Lexington were successfully helped by Alcoholics Anonymous groups in their local communities.30 Communication with members who had left Lexington came through an Addicts Anonymous newsletter, The Key, which was published by members working in the Narcotics Farm’s Vocational and Educational Unit.31 This newsletter discussed issues of concern to those undergoing treatment in Lexington or who were readjusting to community life as a person in recovery.

The spread of Addicts Anonymous from institutional settings to the community began with one man, Danny C., who like Houston S., became something of a recovery evangelist.

Danny C.: The Rise and Fall of the First NA

Danny C. was born July 7, 1907, in Humacao, Puerto Rico. F ollowing the death of both his parents in Danny’s early childhood, he was taken in by a physician and later relocated to St. Joseph, Missouri. There, Danny lived a fairly uneventful life until his first exposure to opiates sparked a 25-year addiction to morphine and heroin.32

At the age of 16 my foster mother, who was a staff physician in the hospital where we resided, gave me morphine for the relief of pain caused by an abscessed ear. I liked the feeling the morphine gave me and, after the operation, when the drug was no longer administered, I asked for more, but was refused. I knew where the pills were kept, and helped myself to them, not even knowing what narcotics were.33 His mother arranged for treatment for Danny and even moved to an isolated rural community where she thought he would be free of temptation—all to no avail. Danny spent nine of his next twenty years in prison on drug-related convictions.34

Danny C. was among the first patients admitted in 1935 to the newly opened U.S. Public Health Service Hospital for addicts in Lexington, Kentucky. It was the first of his eight admissions over the ensuing 13 years. Following a suicide attempt and final re-admission in 1948, Danny participated in Addicts Anonymous meetings and had a profound spiritual experience that served as a catalyst for his sustained recovery.35 It was during this time that He called the new group Narcotics Anonymous (NA) to avoid the potential confusion of two AAs.38 The NA created by Danny C. was not the NA that exists today, but Danny’s efforts first brought the NA name to national attention.

The first NA meeting was held at the Women’s House of Detention, 39 and it was there that Danny met Major Dorothy Berry of the Salvation Army. Major Berry offered NA the use of the Lowenstein Cafeteria in the Salvation Army located on 46th Street in the area of New York City known as Hell’s Kitchen. By January 1950, the first community-based 12-Step meetings were started for addicts.40,41 Major Berry, who became Director of the Eastern Territorial Correctional Service Bureau for Women in 1945 a nd later worked with female addicts at the House of Detention, was NA’s first patron.42,43 A corner of her office was the New York-based NA’s first headquarters.

The application for the incorporation of Narcotics Anonymous is dated January 25, 1951. Danny also created an organizational umbrella for NA—the National Advisory Council on Narcotics (NACON)—and organized an educational support group for parents of addicts (Committee for Medical Control of Narcotics Addiction).44 NACON mailings listed Danny’s full name as the Founder of NA and listed a board of directors that included Marty Mann of the National Committee on Alcoholism and Dr. Marie Nyswander, later co-developer of methadone maintenance. In 1953, NACON was unsuccessful in its attempt to solicit funds to support plans for a public education campaign and developing hospitals for the treatment of drug addiction. 45

Early NA efforts were plagued by a lack of money and meeting space, perceptions by some in the community that NA was just a ruse for addicts to meet to exchange drugs and connections, and fear among addicts that NA was infiltrated by police undercover agents and informers.46 F ew organizations welcomed the new group. F ollowing the closing of the Salvation Army cafeteria, NA meetings were held on the Staten Island Ferry until meeting space was found at the McBurney Branch of the YMCA.47 An open meeting was held every Tuesday night with 10-30 persons attending, and a closed meeting (“ex-addicts only”) was held every Friday night that drew more than 25 persons.48 When NA celebrated its first anniversary in 1951, six members had achieved a year of sustained recovery.49 Three years later, a total of 90 members had achieved stable, drug-free living.50 D anny continued to lead New York NA meetings until his death at age 49 on August 19, 1956.51

Following Danny’s passing, leadership within NA passed to Rae L., who worked for the Narcotics Coordinator’s Office of the New York City Department of Health52—the first NA member working in a paid role within what would soon be an emerging field of community-based addiction treatment. L ater support was also provided by non-addicts, such as Father Dan Egan, who was also known as the “Junkie Priest.” Father Egan was ordained in 1945 and sustained a special ministry to the addicted (and later to people with AIDS) until his death at age 84 in 2000.53 T he New York NA group remained relatively small, with only 4 meetings a week in 1963, but there was some NA growth reported outside of New York City in Newark, Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Vancouver, Canada. In 1965, the New York-based NA reported “chapters” in 14 c ities, 10 states, and 3 foreign countries.54

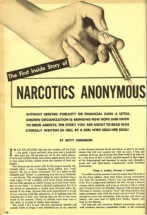

The first NA literature from Danny C. and the New York group—the pamphlet Our Way of Life- An Introduction to NA—was published in 1950. 55 During the 1950s and early 1960s, New York NA, as well as the Lexington-based Addicts Anonymous, achieved considerable visibility in prominent newspapers (the New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, the New York Post, and the Chicago Sun Times), magazines (the Saturday Evening Post, Time, Newsweek, Look Magazine, Family Circle, Confidential Magazine, Down Beat Magazine), and in books bearing such titles as Narcotic Menace, Merchants of Misery, The Junkie Priest, Monkey on My Back, Mainline to Nowhere, Narcotics: An American Plan, and The Addict as a Patient.

After Danny’s passing, NA was promoted in New York City through pamphlets authored by Fr. Dan Egan in which he characterized addiction as a “disease of the whole person— physical, mental, emotional and spiritual” and suggested NA as its best solution.56 Other publications related to NA included the N.A. Newsletter, produced in the early 1960s by the Fellowship House group at St. Augustine’s Presbyterian Church in the Bronx.57

Growth of NA outside of New York City is illustrated by events in Cleveland. Marvin S. had been treated in the U.S. Public Health Service hospitals in Lexington and Fort Worth, Texas. While at Lexington, he participated in Addicts Anonymous, serving as secretary of the Men’s group in 1962.58 Upon his return to Cleveland, he attended AA meetings and helped start a local NA group under the organizational sponsorship of Captain Edward V. Dimond of the Salvation Army Harbor Light Center. Weekly meetings began November 6, 1963, but ceased in late 1964 when meeting attendance plummeted following Marvin’s relapse and return to Lexington59 (Marvin later helped organize NA in the Miami/West Palm Beach area of Florida).60 NA meetings in Cleveland resumed in 1965 and continued until they were disbanded on October 1, 1970, due to “other groups now providing service in this area.”61

The NA created by Danny C. and others existed not as an organized fellowship but as isolated groups lacking connection through a common service structure. S ome of the groups even chose names other than Narcotics Anonymous. The Chicago group, for example, referred to itself as Drug Addicts Anonymous. While attempts to adapt AA’s Steps are evident across these groups, there is a marked absence of references to the use or adaptation of AA traditions, which were first formulated in 1946 and formally adopted by AA in 1950.

Because of the lack of a central service structure, it is unclear how many NA groups actually spread from the original New York-based NA. E vidence of these groups exists primarily within the oral history of later NA groups and as artifacts in NA archival collections. The early NA groups spawned under the original leadership of Danny C. dissipated in the mid-1960s and early 1970s in the wake of harsh new anti-drug laws and the death of Rae L. in 1972. But a new NA—NA as it is known today—was poised to rise on the West Coast.62 For the beginnings of that story, we must return to Los Angeles in the early 1950s.

Betty T., Jack P., and the West Coast AA/Lexington Connection

Betty T. left treatment at the Narcotics Farm in 195063 and shortly thereafter began correspondence with Houston S., Danny C., and AA co-founder Bill W. about her interest in starting a support group meeting for addicts in Los Angeles. B etty, a nurse, was addicted to narcotics and then alcohol and Benzedrine before beginning her recovery in AA on December 11, 1949.64 Her interest in starting a recovery support group for addicts grew out of her own personal background and the growing number of people in AA she witnessed experiencing problems with drugs other than alcohol. O n February 11, 1951, B etty hosted the first Habit Forming Drugs (HFD) meeting at her home—a special closed meeting for AA members who were also recovering from other drug addictions. T hese meetings continued weekly, then monthly, then as a special meeting for newcomers hosted as needed over the next few years.65

Betty became concerned over whether such a special meeting within AA or a special group separate from AA was needed. She discussed this question in a series of letter exchanges with AA co-founder Bill W. in 1951 and 1957, sharing her growing sense that a separate group was not needed for AA members with drug problems. She agreed with Bill W. that addicts who were not also alcoholics could attend open AA meetings but could not become AA members or attend closed AA meetings. That left open the need for a group for “pure addicts,” but Betty felt she was not the person to start such a group, that Addicts Anonymous was not being accepted in Los Angeles, and that Danny C.’s New York-based Narcotics Anonymous groups were not adhering to the Twelve Traditions (e.g., Danny C.’s use of his full name in the press).66 She particularly objected to new groups that dropped “alcohol” from the Steps: “They do not stress the danger of alcohol as a substitute for drugs!”67

The exchanges between Betty T. and Bill W. afford a window into the ambivalent attitudes of AA members toward drugs other than alcohol. Betty was quite candid about the “pill problems” she was observing in AA, and she was encouraged early on by the effects the HFD group was having on AA:

Throughout the L.A. area and as far down as San Diego the addict [who also admits he or she is powerless over alcohol] is one of us...many older members of AA that never told of a problem with drugs, are openly speaking of it at the meetings...I know that many narcotic and barbiturate addicts are sponsored in various groups by members of AA, and they never see an addicts group!68

Bill W., for his part, frequently noted the strong mutual aversion between alcoholics and “dope addicts” and reported that in some areas there had been “violent opposition to drug addicts attending AA meetings.”69

Such ambivalence and resistance is evident in early AA newsletters of this period. For example, the 1953 issue of the The Night Cap, a newsletter from the Central Committee of Alcoholics Anonymous in San Antonio, Texas, notes: “It is our studied conclusion that there is no place in the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous for the narcotic or barbiturate addict.”70 In a 1954 issue of The Key, a patient describes attitudes toward addicts in Las Vegas AA meetings: “all manner and kinds of people are made welcome, the thieves, conmen, crooked gamblers..., but ‘NO DOPE ADDICTS’ are permitted there.”71 Such declarations did not change the fact that many people addicted to drugs other than or in addition to alcohol were finding recovery within the fellowship of AA.

Dr. George M. forwarded Anne’s reply to Betty T., sparking a flurry of letters between her and the GSH and Bill W. on such issues as the distinction between “dual problem alcoholics” and “simon-pure alcoholics,” dissension caused by straight addicts “making testimonies” in AA meetings, the question of need for ”dual purpose groups” (i.e., alcoholism and sedative use; alcoholism and depression), whether alcoholism is a condition distinct from other drug addiction, and the decision to remove the Habit Forming Drugs Group from the AA world directory.

Bill wrote:

Therefore the friction has sprung up, here and there, that an alcoholic is a narcotic, even though he has no sedatives or drugs. And, vice versa narcotics who never guzzled a pint of liquor, sometimes claim they are alcoholics, because alcohol is a narcotic. Personally I think this is kind of a rationalization that won’t work practically and at best it’s only a half truth. Supposing that a homosexual to say I’ve never had an alcoholic history but I do have a compulsion. Alcoholics also have a compulsion therefore I’m an alcoholic. That would be absurd, wouldn’t it? Therefore for AA purposes I think we have to forget about the theory that alcoholics are narcotics and narcotics are alcoholics. A single person may have both addictions. But if he only has one it doesn’t mean that he has the other.

He went on in this communication to share his decision to write an article for the Grapevine to show “where AA begins and where it leaves off in these matters.”74 The February 1958 issue of the Grapevine included Bill’s promised article, Problems Other Than Alcohol: What Can Be Done About Them? The article, by clarifying the boundaries of AA’s primary purpose, set the stage for the later development of a distinct NA fellowship.

Betty T. was not the only one writing Bill W. in these years about the problem of drug addiction. L ynn A. corresponded with Bill W. about a Narcotics Anonymous meeting she started on December 23, 1954, in Montreal after correspondence with Danny C. At the heart of her letters was the proposal that use of the term “addiction” instead of “alcoholism” could further widen the doorways of entry into recovery and allow AA to help a greater number of people. She even pleaded with Bill to concede that he was an alcohol addict.75

As noted previously, Bill struggled with the ability for addicts to become AA members and often attributed this to perceived differences between alcoholics and addicts. But Bill was convinced that alcoholics and addicts could not be mixed, as he suggested in the following anecdote:

The failure has to do with an almost inexplainable (sic) distrust and dislike of alcoholics and addicts for each other. It is an absurd and crazy business, but a fact nevertheless. One day, years ago, I met a man in the corridor of Towns Hospital, where I used to go as a patient. I was there on a 12-Step job. I asked him for a match to light my cigarette. Hauntingly he drew himself up and said, “Get away from me you goddamn alcoholic.”76

In July of 1952, Jack P., a member of AA’s Los Angeles Institutional Committee, sent a letter to Bill W. informing him of a request that had come to AA from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department to help start a “Narcotics Anonymous” group in the Women’s Division of the County Jail. J ack asked Bill for copies of existing literature on narcotics published by t he Alcoholic Foundation; a list of known groups for “narcotics”; and any “thoughts, ideas, advice and knowledge” that might be helpful.77 Jack went on to note that he and Mrs. Bea F., chair of the local AA Institutional Committee, were helping start such a group as private individuals and not as A A members.78 Bill W. expressed interest in this “narcotics project” and went on t o elaborate on his earlier stated views:

Their experience indicates that the narcotic who was formerly an alcoholic can transmit straight to the narcotic himself. To a narcotic, that is, who was never an alcoholic. However, that doesn’t mean that you people in L.A. can’t jump the gap. I certainly think you ought to try though I agree it should not be in the least under A.A. auspices. For some reason hard to fathom alcoholics do not care for narcotics. And narcotics as a class disdain us – they think we’re gutter snipes!79

About ten months passed between Bill’s letter and the next known development in the formation of an actual group. In the middle of June 1953, the planned meeting of NA was held at the Unity Church on Moorpark Street in Van Nuys.80 One of the AA members attending was Jimmy K., who took over the leadership of this group in July of 1953.81 Jimmy would later say, “...we started long before NA was a reality, even in name...we grew out of a need and we found those of us who were members and had come into AA and found we could recover.”82 Another group that met briefly in the early 1950s was called Hypes and Alcoholics (HYAL), some of whose members were later involved in the founding of Synanon—the first ex-addict-directed therapeutic community.

When Bill W. was repeatedly asked for guidance on s tarting groups for “mainline addicts,” he suggested that “bridge members” (AA members who were also recovering from drug addiction) could serve as catalysts to develop such support. 83 As it turns out, that is precisely what happened. The man who served as this bridge in the summer of 1953 was Jimmy K.—widely considered the founder (or co-founder) of NA as it exists today.84

Jimmy K. was born April 5, 1911, to James and Lizzie K. in Paisley, Scotland, his family having first migrated from Ireland in the mid-1830s. T he K. extended family was a close-knit Irish Catholic clan in which drinking, singing, dancing, and storytelling were woven into the fabric of daily life.85 As a ch ild, Jimmy K. befriended a Mr. Crookshank, the “town drunk.” When Jimmy later visited Mr. Crookshank in a local asylum, he vowed to his mother that he would one day help men like Mr. Crookshank.86 What would have been unclear then was the arduous path required to fulfill that oath.

Jimmy’s father migrated to the United States in 1921, and two years later, Jimmy, his mother, and four younger siblings joined him. The family settled first in a working class neighborhood in northeast Philadelphia and later relocated to California. Jimmy progressed from sneaking sips of paregoric and altar wine as a child to daily runs of whiskey and pills through his young adulthood. A self-described “lone wolf,” Jimmy’s excessive use of codeine, pills, and alcohol had left him “bankrupt physically, mentally and spiritually” and an “abject failure as a man, a husband, and a father.” 87 It was in that state that he began his recovery in Alcoholics Anonymous on February 2, 1950.

Like Houston S., Danny C., Betty T., and Jack P., Jimmy developed a passion for helping others recover. Every encounter for him was an opportunity for service. Jimmy’s daughter Cathie recalls an incident in which an intoxicated driver crashed into her car while it was parked in front of the family home. Jimmy brought the drunken man into his home, offered him a cup of coffee, and as the police took him away, encouraged the man to get some help and offered his assistance.88 An NA member would later say of Jimmy, “There was something very magical about the way Jimmy carried the message—when people got close to him, their natural inclination was to recover.”89

When Jimmy K. began attending AA in 1950, he introduced himself as an “alcoholic addict” and developed an early interest in helping those with multiple addictions. He attended early meetings of Habit Forming Drugs and Hypes and Alcoholics and communicated with Danny C. in the early 1950s about the NA group that Danny had started in New York City.90 In a 1984 interview, Jimmy K. indicated that he had corresponded with Danny and that he was concerned that there was no ongoing NA group in NYC.91 While in conversation with Dorothy S., another member of AA, Jimmy stated that he needed to write Danny again. Dorothy shared that she had written Danny after Jimmy had shared Danny’s address with her and that she had just received a r esponse dated January 2, 1952. 92 It is assumed that in her letter to Danny, Dorothy requested copies of their booklet Our Way of Life because Danny responded that they were temporarily out. Danny did include a copy of Facts About Narcotics—a four-page educational pamphlet.”93

The 1984 interview with Jimmy and correspondence from Danny C. to Dorothy S. clearly establish an awareness of and influence of Narcotics Anonymous in New York City upon the efforts to start a group for addicts in North Hollywood, California, but the nature of that influence is difficult to assess. Jimmy would later state that the only thing the California group took from NA in New York was the name.94

On August 17, 1953, the first organizational meeting of the group met at 10146 Stagg Street, Van Nuys, California, with six people present (Frank C., Doris C., Guilda K., Paul R., Steve R., and Jimmy K.). Jimmy K. was nominated as president September 14, 1953. Since the AA name could not be used, the name was changed to Narcotics Anonymous—a name suggested by Jimmy based on his knowledge of NA in New York City.95 The NA bylaws passed August 17, 1953, state: “This society or movement shall be known as Narcotics Anonymous, and the name may be used by any group which follows the 12 steps and 12 traditions of Narcotics Anonymous.”96 An “Our Purpose” statement was incorporated into the NA bylaws from The Key:

Our Purpose

This is an informal group of drug addicts, banded together to help one another renew their strength in remaining free of drug addiction.

Our precepts are patterned after those of Alcoholics Anonymous, to which all credit is given and precedence is acknowledged. We claim no originality but since we believe that the causes of alcoholism and addiction are basically the same we wish to apply to our lives the truths and principles which have benefited so many otherwise helpless individuals. We believe that by so doing we may regain and maintain our health and sanity.

It shall be the purpose of this group to endeavor to foster a means of rehabilitation for the addict, and to carry a message of hope for the future to those who have become enslaved by the use of habit forming drugs.97

Minutes of early meetings reflect concern for traditions, establishment of closed and open meetings, restriction of speakers to those recovering from drug and/or alcohol addiction, and plans for a wide variety of community promotional activities (e.g., development of signs, meetings with heads of Narcotics Divisions of local Police Departments, outreach to social workers, lectures in local schools, newspaper ads.98 An ongoing meeting established by the NA organizational committee, with the first meeting held October 5, 1953, at Cantara and Clyborn Streets at a place called “Dad’s Club” in Sun Valley, California. Twenty-five people attended. Attendance at early meetings ranged from 10-35. In a further connection to pre-NA roots on the east coast, a collection was taken up some time in late 1953 for Jimmy to attend a conference at Lexington.99

Many problems plagued this early effort. Personality conflicts ensued, and all original members of the NA organizing committee had resigned their leadership positions by the end of 1953. Negotiations with local police were required to minimize surveillance and harassment of those attending meetings. T he first NA group moved to “Shier’s Dryer”—a sanitarium for alcoholics100—and NA members continued to attend AA meetings in addition to the one NA meeting per week. M ost people entering NA at this time were heroin addicts, and people approaching NA without a history of heroin injection were viewed as having questionable addict credentials.101 As one early NA member describes:

We came strictly from the streets, if they used anything other than heroin, we didn’t think they were addicts for real. Cause our definition of an addict was that person who stuck that spike into his arm.102

NA meetings were often held in people’s homes for lack of any place else to meet—a coffee pot and set of Depression glass cups moving from location to location.103 Jimmy K. continued his contact with NA during these early years, but avoided leadership roles due to his alarm over changes that were occurring within NA.

There were significant differences between the modes of operation in New York and California NA groups. New York NA members, more “pure” morphine or heroin addicts, had little concern about alcohol and little contact with AA. In contrast, three of the California founders of NA had histories of alcohol and other drug addictions, brought in prior affiliations with AA, and emphasized strict adherence to the Steps and Traditions as adapted from the AA program. When NA groups veered from those principles, those so-called “bridge members” left

NA and returned to AA. Danny C.’s east coast meetings and the west coast groups shared the name Narcotics Anonymous, but they were not the same organization, with East Coast NA exerting only a peripheral influence on the west coast NA that evolved into NA as it is known today.

The new NA that was rising on the west coast maintained a fragile existence throughout its first six years, but its future was by no means assured. One of the things that influenced its fate was a choice of words.

The Steps

The adaptation of the Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous as a guide to recovery from other drug addictions is not as straightforward as it might seem, and the nature of these adaptations exerted a profound influence on the subsequent history of NA and the larger arena of addiction recovery.

Lacking enduring leadership in the face of constant patient turnover at Lexington, the Steps of Addicts Anonymous vary across time. A 1951 volume of The Key presents Steps One and Twelve as follows:

Step One: We admitted we were powerless over alcohol and drugs—that our lives had become unmanageable.

Step Twelve: Having had a spiritual experience (or awakening) as a result of these steps, we try to carry this message to alcoholics and addicts and to practice these principles in all our affairs.104

Here, we see a substitution of the phrase “alcohol and drugs” for AA’s “alcohol” in Step One and “alcoholics and addicts” for AA’s “alcoholics” in Step Twelve. By 1959, The First Step read, “We admitted we were powerless over drugs...that our lives had become unmanageable,” and the Twelfth Step read, “carry this message to addicts.”105

Members of the Habit Forming Drugs group in Los Angeles, as a special meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous, used AA’s Twelve Steps, but Betty T. did pen “12 Suggestions That May Be of Help to Anyone Addicted to Drugs.” Her suggestions emphasized the absolute and permanent (“no compromise”) need to abstain from alcohol, drugs, and all medications not prescribed by a physician knowledgeable about addiction.106

Since the early New York-based NA existed as independent meetings without a unifying service structure, the Steps varied by group. Most early New York City NA meetings, as well as Cleveland NA (1963), used the Twelve Steps that were outlined in the Addicts Anonymous pamphlet, Our Way of Life, which substituted the phrase “powerless over drugs” for the phrase “powerless over alcohol” in Step One, and substituted “carry this message to narcotic addicts” for “carry this message to alcoholics” in Step Twelve.107

A Thirteen-Step version can be found in the early 1960s literature of NA groups from Fellowship House in the Bronx and in a newsletter from the New Look Group of Narcotics Anonymous held at the State Prison of Southern Michigan (Jackson, Michigan)—the latter one of several prison groups Rae L. helped start by mail.108

- Admit the use of narcotics made my life seem more tolerable, but the drug had become an undesirable power over my life.

- Come to realize that to face life without drugs I must develop an inner strength.

- Make a decision to face the suffering of withdrawal.

- Learn to accept my fears without drugs.

- Find someone who has progressed this far and who is able to assist me.

- Admit to him the nature and depth of my addiction.

- Realize the seriousness of my shortcomings as I know them and accept the responsibility of facing them.

- Admit before a group of N.A. members these same shortcomings and explain how I am trying to overcome them.

- List my own understanding of all the persons I have hurt.

- Take a daily inventory of my actions and admit to myself those which are contrary to good conscience.

- Realize that to maintain freedom from drugs I must share with others the experiences from which I have benefited.

- Determine a purpose in life and try with all the spiritual and physical power within me to move towards its fulfillment.

- God Help Me! These three words summarize the entire spirit of the 12 preceding steps. Without God I am lost. To find myself I must submit to Him as the source of my hope and my strength.109

Use of the Thirteen Steps by some NA groups on the east coast continued into the mid-1960s. The New Look NA group, which was started in 1959, shifted in 1968 to the use of west coast NA Steps and literature.110

|

Thirteen Steps that appear in the bi-monthly publication for N.A. members at the Southern Michigan Prison in Jackson, Michigan. New Look courtesy of anonymous NA Member |

Within the emerging California-rooted NA, there was considerable debate in 1954 over how to phrase the Steps. Jimmy K. prevailed in these discussions in getting the phrase “our addiction” inserted into the First Step rather than such alternatives as alcohol and drugs, narcotic drugs, or drugs.111 This is somewhat remarkable in light of the fact that addiction was a word rarely heard in the AA circles that exerted such an early influence on NA.112 This innovation is also of considerable historical significance. NA Trustees would later note:

Drugs are a varied group of substances, the use of any of which is but a symptom of our addiction. When addicts gather and focus on drugs, they are usually focusing on their differences, because each of us used a different drug or combination of drugs. The one thing we all share is the disease of addiction. It [defining NA’s First Step in terms of addiction] was a masterful stroke. With that single turn of a phrase the foundation of the Narcotics Anonymous Fellowship was laid.113

AA, New York-based NA, and later Twelve-Step groups staked their institutional identities and the process of mutual identification on a particular drug choice. In contrast, the NA rising on the west coast in the early 1950s forged its identity and internal relationships not on the shared history of narcotics (the dominant drug choice of early members), but on a shared process of addiction. Jimmy K.’s writings are very clear on this singular point:

Addiction is a disorder in its own right...114--an illness, a mental obsession and a body sensitivity or allergy to drugs which sets up the phenomenon of craving, over which we have no choice, as long as we use drugs.115

This had three effects. First, it addressed the frequently encountered problem of drug substitution by e mbracing renunciation of all drugs, including alcohol, within the concept of recovery. S econd, it opened the potential for people to enter NA with drug choices other than opiates. Third, it explicitly defined addiction as a “disease” and the addict as a “sick” person.

This early understanding is revealed in the Narcotics Anonymous Handbook developed by N A members at Soledad Prison in 1957:

At our meetings of Narcotics Anonymous, we join together in fellowship, where we tell our stories in an effort to arrest our common disease—addiction.116

Here [in NA] we have come to realize that we are not moral lepers. We are simply sick people. We suffer from a disease, just like alcoholism, diabetes, heart ailments, tuberculosis, or cancer. There is no known cure for these diseases and neither is there for drug addiction. But, by following the principles of Narcotics Anonymous completely, we can arrest our disease of addiction to narcotics.117

NA’s definition of the problem as a process of “addiction” that transcended one’s drug choice and required a common recovery process may be viewed by future historians as one of the great conceptual breakthroughs in the understanding and management of severe alcohol and other drug problems. This is all the more remarkable coming at a time that substance-specific disorders were still thought to be distinct from each other, as were their treatment and recovery processes. In addiction, NA found an organizing concept similar to the 19th century concept of inebriety and anticipated future professional efforts to create such an umbrella concept (e.g., chemical dependency) and future scientific findings that addiction to multiple drugs is linked to common reward pathways in the brain.

For Jimmy K. to have made this conceptual leap in the early 1950s is a remarkable achievement deserving of wider recognition from the scientific and professional communities. What this meant within the NA experience as NA grew across the country was expressed by one of the early NA members in Philadelphia:

We wanted the door to be as wide open as possible. We wanted to drop all that street shit: “I’m cooler than you because I shot meth, and you just drop Black Beauties.” We had to come to the point: “We’re all addicts. Drugs kicked our asses, and it really doesn’t matter whether you’re strung out smoking reefer every day or you’re shooting a couple thousand bucks of heroin a week.” It’s about addiction—drug addiction.118

The contemporary emergence of “addiction” and “recovery” as conceptual frameworks for the professional field of addiction treatment and as frameworks for the larger cultural understanding of severe alcohol and other drug problems and their resolution is historically rooted in NA’s formulation of its Twelve Steps in 1954. However, this breakthrough did not assure NA’s survival as an organization.

NA’s Near-Death Experience

Between 1953 and 1958, the fledgling NA group in California continued to meet, but meetings were, at best, “periodic or sporadic.”119 Several factors contributed to the dissipation and near death of NA, including NA coming under the influence of Cy M., who took over the chairman role on September 23, 1954.120 Cy was an AA member who had also been addicted to painkillers following wartime combat injuries. Jimmy recruited Cy to be the speaker at the first meeting that was held on October 5, 1953, because of Cy’s history and his previous comments that addicts should find another place to go besides Alcoholics Anonymous.121 Cy’s dominance (he sometimes referred to himself as the “founder of NA”122) and aggressive promotion of NA extended NA’s early reach into places like San Quentin Prison, but the resulting personality conflicts engendered by his leadership style led to the resignation of all of the original founding members.123 Jimmy later described this period:

So, the very first meeting, it wound up, oh God, it was a riot. Everybody was fighting with each other. Within two weeks, we only had one or two people left of the original group.124

Several changes in NA philosophy and practice occurred during Cy’s leadership tenure. The new directions unfolding in these years are indicated by a description of an NA meeting appearing in a November 7, 1957 , article in the San Fernando Valley Mirror. The article describes those at the meeting setting forth a 3-part plan to solve the nation’s drug problem: 1) create a n ationwide network of clinics where confirmed addicts would be administered free drugs under medical supervision, 2) create a “crash program” for treatment and social rehabilitation, and 3) introduce a course in narcotic education into the schools with the goal to “scare the hell out of them.”125 There were also reports during this period that the tenor of NA meetings changed when Cy began using a confrontational “hot seat” technique in the meetings— before such techniques were popularized by Synanon.126

By 1959, the only NA meeting was at Shier’s Dryer, and Jimmy K. had stopped attending that meeting because of his strong feelings on the need for NA non-affiliation and self-support. 127 The notes Jimmy K. would later use to guide his presentations on early NA history contain references to this period that are telling, e.g., “One Man Domination—No Growth,” “Personalities—Resentments, Resignations,” and “new committee almost completely dropped traditions.”128 A critical final turning point in NA’s 1959 c ollapse was Cy and another member (who was suspected of being loaded at the time) appearing on a television show in the fall of 1959. As conflict grew, Cy withdrew from leadership, and NA meetings ceased for a short time.129

When NA ceased meeting in late 1959, Jimmy K., Sylvia W., and Penny K. met to see what they could do to rekindle NA. There were no existing members, no money in the treasury, and no literature.130 NA was reborn when they started the Architects of Adversity NA Group at Moorpark, later known within NA as the “Mother Group.”131 Members came and went in this reborn NA, but it was Jimmy’s tenacious presence that held the group together. Bob B., who was in and out of NA at that time before becoming one of NA’s long-term members, later reflected:

...there was only usually one or two of the old crowd still there at any given time. Every time I’d go out and come back to see who was still there, there was usually Jimmy and one other...Jimmy always seemed to be the one who was always standing there with the door open saying, “Come on in and have a cup of coffee.”132

NA learned painful lessons through its near-death experience, including the dangers of relying on a single, dominant leader, the risks of abandoning adherence to NA Traditions, and the need for a distinctive NA culture. NA was reborn in late 1959 with those lessons in mind. NA’s near-death experience cleaved its history into “before” and “after,” with the phrase “NA as we know it today” used to denote the new NA that rose in 1959 from the ashes of the old.133 As earlier members returned and new members joined, NA began its slow growth into the present. By 1964, N A had grown to a core of 20-25 members in the L.A. area, most of whom had histories of intravenous heroin use and past jail or prison experience.134 The severity and chronicity of their past addictions offered living proof of the transformative power of NA as a framework for long-term recovery.

This collapse and rebirth of NA in California occurred at a time that Addicts Anonymous meetings continued at Lexington and NA meetings continued in New York City and other Eastern cities. Whether any of these groups would survive was still open to question. T o survive and grow, NA—like AA before it—needed a core body of literature to help carry its message and prevent corruption of its basic program.

NA Literature and NA’s Basic Text

The book Narcotics Anonymous, commonly referred to as the Basic Text, is for many NA members as much a part of their recovery as meetings, sponsorship, and service work. NA literature evolved through the substitution of words within or mimicking of AA literature to the emergence of authentic voices of NA recovery experience.

The first generation of literature written by and for addicts originated from the Addicts Anonymous Group in Lexington, Kentucky. Though the exact publication date is unknown, by April 1949, the Addicts Anonymous group had produced the pamphlet Our Way of Life, which was adapted directly from the Alcoholics Anonymous pamphlet, A Way of Life.135 Bobbie B. of the Alcoholics Anonymous General Service Headquarters wrote quite prophetically to Clarance B., secretary of the Addicts Anonymous group:

I have just finished going over the mimeographed booklet “Our Way of Life” and I find it good. Isn’t it wonderful how simple a transition can be made of our Twelve Steps from one illness to another?136

A significant development in the history of literature for recovering addicts occurred between 1954 and 1956 when the California-based NA developed a pamphlet authored by Jack P., Cy M., and Jimmy K. that is variably known as the Little Brown Book, the Buff Book, or the Little Yellow Book.137 In addition to the “addiction” terminology appearing in Step One, the “Just For Today” passage from this pamphlet continues to be a mainstay in many NA meetings.138

Following the near death of NA in 1959, Jimmy K., Silvia W., and Penny K. undertook the writing of new NA literature. Who Is an Addict?, What Can I Do?, What Is the NA Program?, Why Are We Here?, and Recovery and Relapse were all written during 1960, and We Do Recover was completed in 1961. These writings, along with the Steps and Traditions, were consolidated into a publication called the Little White Booklet—also known as the White Book— which was first published in 1961 139 and to which personal stories were added in 1966.140 The White Book served as the primary piece of NA literature for the next 20 years and provided the framework for the later development of NA’s Basic Text.

In 1971, NA Trustees explored the idea of publishing a book intended to be “somewhat analogous to AA’s Big Book.”141 A proposal to just edit the Big Book to read more like an NA publication was rejected, and in 1972, a letter was sent from the “Book Committee” at the NA World Service Office asking the Fellowship for help in preparing a hardcover book to be titled Narcotics Anonymous that would “present the NA program of recovery and way of life in terms that are meaningful to the newcomer who cannot identify with alcoholism.”142 The lack of response to this letter from NA membership provided no means for the Committee to move forward with the book project at that time. A more modest effort emerging from Northern California NA in 1972 was This Is NA, which involved minor word substitution from the This Is AA pamphlet—a fact that led to its later removal as NA literature.143,144

Brown (Buff) Book, which contains the Just For Today reading; the oldest known piece of literature that is still read regularly in NA meetings today. Courtesy of anonymous NA member.

Despite these early 1970s efforts, the only significant literature developments in the next 10 years were five informational pamphlets printed in 1976 (We Made A Decision, So You Love An Addict..., Another Look, Recovery and Relapse, and Who, What, How and Why).145 Renewed effort to create the equivalent of AA’s Big Book for NA came from NA members in Atlanta, GA. The spark for this project was ignited when Bo S. attended the 7th World Conference in San Francisco in 1977 and spoke with many of those present about the need for an NA Basic Text. Bo returned to Atlanta with the support and validation to pursue work on the Basic Text from two influential California NA members, Jimmy K. and Greg P. The book was written between 1979 and 1982 over seven World Literature Conferences that involved over 400 recovering addicts in NA. NA’s Basic Text was approved in 1982 and officially released in 1983.

The writing of the Basic Text was achieved through a massive grassroots effort characterized by inclusiveness and great sacrifice. T he 1st World Literature Conference (Wichita, KS, 1979) resulted in the Handbook for Narcotics Anonymous Literature Committees. The handbook established certain values that guided the process of creating a book for the NA Fellowship. All members were encouraged to contribute material with the hope of being able to create the best possible book.146

Sally E., who attended three World Literature Conferences, recalls barely legible input submitted on a napkin that was carefully deciphered because of its potential import.147 Jim N., who hosted the 2nd World Literature Conference (Lincoln, NE, 1980), needed postage in order to send flyers about the upcoming conference to every known group. Sitting around the kitchen table, he and four other members realized that they had sold blood to support their habits, and they could do the same to support their recovery in NA. They each donated a pint of plasma and received $15.00, which they used to pay for the mailing.148 Registration flyers for upcoming

World Literature Conferences included the option of staying in an NA member’s home.149 During the 3rd World Literature Conference, Greg P. in Oregon dictated an entire chapter over two phone calls that totaled over 9 hours to Molly P. in Memphis, Tennessee. Molly sat on a suitcase while members held the phone to her ear.150, 151 Greg’s phone was disconnected following this effort due to the long-distance expenses incurred.152 Typical of the dedication that went into this process was Doug W., who rode his bicycle from Lincoln, Nebraska to the 6th World Literature Conference in Miami, Florida, staying in NA members’ houses along the way.153

Following the publication of the Basic Text, NA focused much of its publication efforts on It Works – How and Why, a collection of essays on the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. Just for Today, a book of daily meditations, followed closely afterwards. Further efforts included a workbook on the Steps titled The Step

Working Guide and a collection of sponsorship experiences simply called Sponsorship. Currently in development is Living Clean –The Journey Continues, a collection of experiences from NA members—many with twenty, thirty, or more years clean—on a variety of topics that many addicts face as they mature in their recovery.

Similar to other mutual aid fellowships, NA experienced internal conflicts related to its literature approval process, the cost of literature, and the reproduction and distribution of literature by members.154 NA entered uncharted waters in 1990 when a civil lawsuit was brought against one of several NA members who were reproducing and distributing a free, unauthorized version of NA’s Basic Text.155 Individuals involved with the reproduction and distribution of the “Baby Blue” text justified their actions on grounds that the Basic Text was overpriced and that unauthorized changes had been made to the Basic Text without approval from NA groups. The lawsuit finally resulted in a negotiated settlement156 that led to the Fellowship Intellectual Property Trust (policies protecting

NA’s name, trademarks, and recovery literature) and a literature approval process that today involves input, review, and approval at the group level.

NA’s Basic Text was the first substantial piece of literature created by addicts for addicts, and marked the emergence of NA’s own language and culture. It provided a vehicle for NA growth throughout the world, and income from its sales provided the support for NA’s subsequent growth. Since its initial publication, more than 7.3 million copies of the NA Basic Text have been distributed in 18 languages.157

Explosive Growth

NA faced unique obstacles to growth from its earliest days: 1) the problem of members getting high together after spending time in meetings recounting episodes of drug use—before there was a well-developed NA recovery culture, 2) the presence of drug dealers and undercover agents at or near early NA meetings, and 3) the lack of sufficient personal clean time and maturity to sustain the functioning of local groups.158 Jimmy K. reflected on these early days:

Nobody trusted nobody—you know they thought it was staked out. They wouldn’t believe us when we told them there was no surveillance. And we weren’t just too sure in the beginning ourselves.159

After nearly dying in the late 1950s, NA growth extended from five meetings in 1964 to 38 meetings in 1971, 225 meetings in 1976, 2,966 meetings in 1984, 7,638 meetings in 1987, 15,000 meetings in 1990, 19,000 meetings in 1993, 30,000 meetings in 2002, more than 43,900 meetings in 2007, and 58,000 meetings in 2010.160

There are many contributing factors to the growth of Narcotics Anonymous. One that cannot be overstated is the tireless support and encouragement from Jimmy K. to addicts living in communities that lacked NA meetings. Jimmy consistently encouraged lone addicts to start meetings in theirlocal communities.161 He would even record meetings and talks that he would send to emerging groups in order to provide them with the Narcotics Anonymous message of recovery.162 Another significant event was the decision to hold the 8th World Convention in 1978 in Houston, Texas—the first time it had been held outside of California. Growth of NA occurred wherever a World Convention was held as isolated addicts found one another, exchanged phone numbers, and began to see tangible evidence that recovery through NA was a reality.163 The expansion of NA groups was stimulated, in part, by gr owth of the addiction treatment industry and the growing cooperation between NA and treatment institutions. Such cooperation began early, with NA working with the Chrysalis Foundation—the first addiction treatment program to specifically emphasize NA philosophy.164

The profile of members also diversified over the course of NA’s history. The latest (2009) NA membership survey reveals a membership that is gender balanced (58% male, 42% female), predominately middle-aged, ethnically diverse (73% Caucasian, 14% African American, 10% Hispanic, 7% other), and highly productive (71% working full- or part-time, 7% retired, 7% full-time students, 4% homemakers). Members attend an average of 4.2 meetings per week, with 57% of members having 6 or more years of continuous recovery. 165

Comparisons of membership surveys from 1989 to present reveal increased involvement of women and Caucasians in NA and a membership that has more average clean time and is getting older—due in great part to members remaining involved in NA through the transition from recovery initiation to long-term recovery maintenance. This is evident in the growth of average clean years of NA members from 7.4 years in 2003 to 9.1 years in 2007. NA recovery feeds on itself—with those first attending NA due to the influence of an NA member increasing from 29% in 1989 to 58% in 2007. The influence of treatment center referral has also continued to increase between 1989 and 2007.166

Growth of NA outside North America began slowly, with NA meetings in only three foreign countries in 1972, and then accelerated to more than a dozen countries in 1983, 60 in 1993, 127 i n 2007, and 131 i n 2010. NA literature is now available in 39 languages, with translations into an additional 16 languages in process.167 A landmark was reached in 2009, with more NA meetings being held outside the United States than in the United States. Equally remarkable, and deserving of its own written history, is the fact that 28.9% of all NA meetings now occur in one country outside the U.S.—Iran—where NA growth has been explosive since its inception there in 1994.168

The sustained growth of NA exposed long-standing problems with NA’s organizational and service structure—problems NA sought to solve through creation of the NA Tree.

The NA Tree and Beyond

Most of the published literature on recovery mutual aid societies focuses on descriptions of their personal program of recovery, with little attention to how such groups structure and sustain themselves as ever-larger and increasingly complex organizations. The transition from a self-encapsulated recovery mutual aid meeting to a recovery mutual aid fellowship requires a structure for communication (e.g., information dissemination and mutual support between groups), service (e.g., assistance in starting new meetings, literature distribution, collaborating with other organizations), and governance (e.g., collective decision making on issues affecting the fellowship as a whole). T here is in the history of such fellowships a pervasive tension between any founder/leader, national or worldwide governing body, local leaders, and the mass of fellowship members. That tension breeds questions of:

- authenticity (Who best represents the aspirational values of the fellowship?),

- authority (Who has the right to make decisions and/or speak on behalf of the organization?),

- connection (What are the means through which individuals and groups within the fellowship can communicate with each other?),

- assistance (Who is responsible for addressing the needs of local groups, offering support to those wanting to start new groups, and responding to external professional and public requests for information and service?), and

- stewardship (What is the best use of the fellowship’s human and financial resources?).

NA has wrestled with these questions since the first NA bylaws were written on August 17, 1953.169 During the 1960s, an NA Board of Trustees (two NA members and two non-addicts) was created (1964), with the subsequent selection of six NA members to serve as “Permanent Trustees” (1969).170 In 1976, approval of the NA Tree, authored by Greg P. and Jimmy K., established a new service structure that continued to be amplified, revised, and supplemented via:

- an evolving NA Service Manual,171

- the work of key committees (e.g., the World Policy Committee, 1983; the Select Committee on the Service Structure, 1984),172

- efforts to more clearly define the purpose and functions of an NA group (1990),173

- articulation of the guiding principles of NA Service structure (Twelve Concepts, 1992),174

- the creation of new elements of the service structure (e.g., the World Board, the Human Resource Panel, and the World Pool, 1998), and

- a Service System Project (2008) designed to address continuing problems within the service structure at the regional and local level.175

These and other numerous efforts confirm the challenges faced in creating a viable structure that can serve the needs of a rapidly evolving and growing recovery fellowship. Although how that is best accomplished remains a subject of considerable discussion within NA, the ultimate intended purpose of that service structure has become clearer over the course of NA’s history. The 2010 NA World Service Conference adopted the following refined vision for NA Service:

All of the efforts of Narcotics Anonymous are inspired by the primary purpose of our groups. Upon this common ground we stand committed.

Our vision is that one day:

- Every addict in the world has the chance to experience our message in his or her own language and culture and find the opportunity for a new way of life;

- Every member, inspired by the gift of recovery, experiences spiritual growth and fulfillment through service;

- NA service bodies worldwide work together in a spirit of unity and cooperation to support the groups in carrying our message of recovery;

- Narcotics Anonymous has universal recognition and respect as a viable program of recovery.

Honesty, trust, and goodwill are the foundation of our service efforts, all of which rely upon the guidance of a loving Higher Power.

Looking from the outside in, today’s addiction professionals and recovery support specialists might view NA service and support structure as beginning with the individual member attending local meetings hosted by one or more named NA groups. Sponsor-sponsee relationships (mentorship of new members) take place in the context of these meetings, and it is common for members to select a home group that they regularly attend and at which they can vote on matters of group conscience affecting the home group or NA as a whole. Members in each home group have the opportunity for service in many roles, both formal and informal. Members who pursue such service work are referred to as trusted servants. Formal service positions, which are generally elected positions through group conscience, include secretary, treasurer, group service representative (GSR), and GSR-Alternate. Examples of informal positions, which some consider the highest level of service, include opening the meeting door, making the coffee, putting out the literature, leading the meeting, and greeting people at the door.

Local NA groups form an Area Service Committee to provide coordinated NA services for a p articular geographical area and to carry the conscience of the groups to Regional and World levels. Area Service Committees elect their own trusted servants (Area Chairperson, Vice Chairperson, Secretary, Treasurer, and Regional Committee Member) and also maintain standing service committees such as:

- Public Relations Committee (PR)/Public Information (PI) – informs the public, prospective members, and professionals about Narcotics Anonymous through local NA web pages, printed meeting schedules, phone lines, and fellowship development (outreach).176

- Hospitals and Institutions (H & I) Committee – carries the NA message to those who do not have access to NA meetings in the community, e.g., those in hospitals, treatment centers, or correctional facilities.

- Convention Committee – raises money and plans an Area NA Convention.

- Activities Committee – promotes unity in the fellowship through events such as dances, cook-outs, celebrations, and speaker jams.

- Policy Committee – maintains local policy and procedure for the Area Service Committee.

- Literature Committee – participates in input and development of new literature and maintains an adequate supply of literature available to groups at Area Service Meetings.

Standing committees will vary from Area to Area. Similar to the structure and function of Area Service Committees, Regional Service Committees are comprised of Areas from a p articular geographical area.

The operational chart changes at the World Level from how most, but not all, Regions and Areas provide service. Narcotics Anonymous World Services (NAWS) is comprised of the World Board and the World Service Office (WSO). The World Board, WSO, and Regions work together to hold the World Service Conference every two years, where issues of importance to the worldwide NA fellowship are discussed. There are no standing Committees at the World Level. Instead, a task (e.g., writing new literature) is voted on by members of the World Service Conference (Regional Delegates, World Board, and Human Resources), and if approved, the Human Resource Panel draws from the World Pool NA members they think will be the most qualified to be on a workgroup to complete the approved task.

The Narcotics Anonymous World Service structure signifies another level of differentiation from Alcoholics Anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services consists of groups, districts, and areas from the U.S. and Canada that participate in an annual General Service Conference. There are 58 autonomous International General Service Offices listed on the AAWS, Inc. website that do not participate in the North American General Service Conference. Narcotics Anonymous World Services consists of groups, areas, and regions from the entire world that participate in a World Service Conference every two years. Zonal Forums have become an important vehicle for NA communities from around the world to participate in service-oriented sharing, communicating, cooperation, and growth. While existing outside of NA’s formal decision-making system, zonal forums help developing and emerging NA communities and make contributions at the World Service Conference.

As can be seen from this brief summary, decision making at the level of World Services has become increasingly complex in tandem with NA’s growth (from support for 2,966 meetings located primarily in the United States in 1983 to support for today’s 58,000+ meetings in 131 countries). While tensions still exist within NA, there has been significant maturation in the service system. As the service system continues to evolve, Narcotics Anonymous will continue to strive for better communication, more inclusiveness, less redundancy, greater efficiency, and more assertive outreach to the still suffering addict.

What is important for the student of recovery is that such struggles reflect normal, although potentially distressing, growing pains of recovery mutual aid societies. The ultimate tasks of such coming of age involve decentralizing leadership, surviving the passing of the first generation of pioneers, achieving and protecting organizational autonomy, maintaining mission fidelity, and developing a viable and evolving service structure.

NA Comes of Age

Throughout much of its history, NA existed in the shadow of AA—the stepchild of its famous parent. NA’s predecessors, such as Addicts Anonymous, drew their Steps framework of recovery from the Twelve Steps of AA, and their meeting formats mirrored AA meetings, e.g., use of the Serenity Prayer and Lord’s Prayer.177 The NA that exists today was founded by “bridge members” of AA who based the NA program of recovery on AA’s Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions and who used AA participation as a support for their own recoveries. Interviews with early NA members are replete with references to reading AA literature, having AA sponsors, attending AA meetings—even meetings with two podiums, one on which was listed the Twelve Steps of AA and the other draped with the Twelve (or Thirteen) Steps of Addicts Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous.178

During its first two decades, many NA members also attended AA meetings. As Dave F., a member of early NA in Pennsylvania, reports:

...everybody went to AA. Nobody would have even attempted—it would have been viewed as foolhardy and half-stepping—to try to stay clean solely on NA meetings. NA members simply didn’t have the clean time.179

NA literature, NA meeting rituals, and the larger culture of NA developed in the shadow of AA. But a “purist movement”180 and, more importantly, a larger consensus emerged within NA in the mid-1980s that challenged NA to step away from AA’s shadow and distinguish itself as a distinct recovery fellowship. This process began in the early 1980s, but was perhaps most exemplified in a 1985 communication from NA Trustees entitled, “Some Thoughts on Our Relationship with A.A.” This communication, written at the request of Bob Stone by a WSO staff writer and subsequently reviewed and published by the Trustees in the WSO’s Newsline, opened with an acknowledgement of NA’s gratitude to AA. It noted NA’s departure from AA in the choice of language used in NA’s First Step and then elaborated on this important divergence:

The A.A. perspective, with its alcohol oriented language, and the N.A. approach, with its clear need to shift the focus off the specific drug, don’t mix very well....When our

members identify as “addicts and alcoholics,” or talk about “sobriety” and living “clean and sober,” the clarity of the N.A. message is blurred. The implication in this language is that there are two diseases, that one drug is separate from the pack, so that a separate set of terms are needed when discussing it. At first glance this seems minor, but our experience clearly shows that the full impact of the N.A. message is crippled by this subtle semantic confusion.181

This communiqué went on to define the essential NA message:

We are powerless over a disease that gets progressively worse when we use any drug. It does not matter what drug was at the center for us when we got here. Any drug use will release our disease all over again....Our steps are uniquely worded to carry this message clearly, so the rest of our language of recovery must be consistent with those steps. Ironically, we cannot mix these fundamental principles with those of our parent fellowship without crippling our own message.182

The communiqué then called for a distinct NA culture:

...each Twelve Step Fellowship must stand alone, unaffiliated with everything else. It is our nature to be separate, to feel separate, and use a separate set of recovery terms, because we each have a separate, unique primary purpose....N.A. members ought to respect our primary purpose...and share in a way that keeps our fundamentals clear...Our members who have been unintentionally blurring the N.A. message by using drug-specific language such as “sobriety,” “alcoholic,” “clean and sober,” dope fiend” etc. could help by identifying simply and clearly as addicts and using the words “clean, clean time and recovery” which imply no particular substance. And we all could help by referring to only our own literature at meetings, thereby avoiding any implied endorsement or affiliation. Our principles stand on their own.183

The statement was presented at the NA World Service Conference in 1986 and became World Service Trustee Bulletin #13.